History is a collection of stories. These stories connect us to the past and help us form our identities that are rooted in places. Let’s explore what Edmonton was like decade by decade.

These artifacts from the City of Edmonton Heritage Collection are from the 1920s.

Jump To: Introduction | Freedom of Movement | Conditions on Freedom of Movement | Costs of Freedom of Movement | Conclusion

One of the defining characteristics of the 1920s is freedom of movement. In Edmonton, the increased desire for freedom of movement arose largely due to changes in technology and social shifts. For those who had either survived or grown up through the First World War and the 1918 influenza epidemic, difficult challenges and loss had become common experiences. Heading into a new decade, many felt a new urgency for change and a desire for more freedoms.

Social shifts that saw increased mobility in women’s clothing are the most common example, which visually illustrates the freedom of movement that was characteristic of the 1920s. Women’s fashion changed from structured, fitted, full-length dresses, to dropped waist, loose-fitting, shorter hemline dresses. These changes allowed not only more physical mobility, but also represented a slight relaxing of social norms for women’s clothing. This social shift is often referred to as Flapper Culture.

While Flapper Culture was present in Edmonton, the technological advances in transportation arguably brought about more significant changes to freedom of movement. Edmonton experienced increased quality, quantity, and access to transportation methods in the 1920s. Some people were able to more easily move within the City of Edmonton, to leisure travel outside of Edmonton, and to increasingly migrate from rural to urban areas like Edmonton.

The Edmonton in the 1920s exhibit will focus on freedom of movement related to transportation and social dynamics. It will discuss how such freedoms were often conditional, not equitably available, and often came at a cost to the natural environment.

Automobiles first started arriving in Edmonton in the early 1900s, but their numbers increased rapidly in the 1920s. As cars became more common, so did activities like autocamping, where people drove into the wilderness and attached tents to their cars, or went to campgrounds newly designed to accommodate cars.

Tourism by car became a more accessible getaway, particularly for those who couldn’t afford tourism by train. Automobiles provided increased ease and freedom to move within and outside of Edmonton. At least when their availability and the condition of the roads would allow!

Picnic set popular for autocamping [City of Edmonton Heritage Collection 1985-000-6815A-O]

In the 1920s, many farmers in the Edmonton area transitioned from horses to tractors. Much like how cars were replacing horse-drawn carriages, tractors were replacing horse-drawn farm implements to do farm work faster, and on a larger scale. The unstable economic conditions of the decade pushed farmers to use more and more land in order to make profits. At the same time, tractors were becoming more readily available.

Advance-Rumley OilPull H16/30 Kerosene Engine Tractor [City of Edmonton Heritage Collection 1967-430-7045 A 1921]

The train first reached Strathcona (south side of the river) in 1891, and Edmonton (north side of the river) in 1902. The use of trains also continued to grow through the 1920s when the new Canadian National Railway station was built in 1928 on 104 Ave and 100 St.

Train access to Edmonton allowed for a dramatic increase in the movement of people and goods to Edmonton.

Postcard of Canadian National Railway Station built in 1928 and Queen’s Avenue School on 104 Ave and 101 St., created 1930 [City of Edmonton Archives EA-10-931]

Find Out More:

Edmonton CNR Railway Stations

Edmonton experienced ups and downs in the popularity and use of airplanes throughout the 1920s. Blatchford Field became Canada’s first municipal air harbour in 1926, but by the end of 1928, Edmontonians voted against an expansion of the airport. However, after the Mercy Flight out of Edmonton in January 1929, where pilots Wop May and Vic Horner brought diphtheria antitoxin to Fort Vermillion to treat an outbreak, the City Council authorized expansion funds for Blatchford field anyway.

Airplanes provided a new form of movement that was generally faster, further reaching, and could access areas that automobiles or trains could not.

Find Out More:

This 1922 article in the Edmonton Bulletin refers to Edmonton as “The Gateway of the North.”

The radial railway system for streetcars began service in Edmonton in 1908. However, it reached its greatest extent of routes in 1920 and experienced its highest ridership in 1929. For a base fare of $0.05, people could move within Edmonton more easily.

Special observation streetcar that operated until 1925 [Provincial Archives of Alberta, A4848]

Find Out More:

Edmonton Radial Railway Society

Automobiles, trains and airplanes brought freedom to many, but these growing modes of transportation, particularly trains, were also tools of oppression which brought Indigenous children to residential schools. In 1924, the federal government opened the Edmonton Indian and Residential School at St. Albert. Residential schools such as this one greatly restricted the movement and freedoms of Indigenous children who were removed from their homes and were subjected to numerous hardships and abuses in an attempt to eradicate Indigenous cultures and populations.

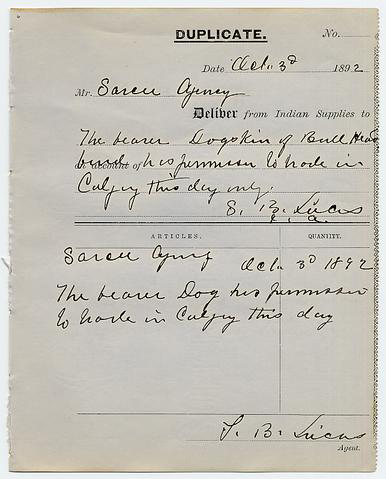

Additionally, outside residential schools, Indigenous people were restricted to reserves, where a federal government agent determined their movement off of the reserve boundaries through a Pass System. Although the example below is from prior to the 1920s, the Pass System remained in effect into the 1930s and 1940s, depending on the location.

Reserve Pass, 1892 [Glenbow m-1837-22A-p06]

Writing on pass reads: “Oct. 3rd, 1892. Sarcee Agency. The bearer Dogskin of Bull Head band has permission to trade in Calgary this day only. S.B. Lucas I.A. Sarcee Agency. Oct. 3rd 1892. The bearer Dog has permission to trade in Calgary this day. S.B. Lucas”

Find Out More:

The Pass System Documentary

Due to the resiliency of Indigenous communities, Edmonton and the surrounding area is home to many Indigenous people today. Among many positive contributions, Indigenous art amplifies Edmonton’s city scape and can play a helpful role in reconciliation.

Tawatinâ Bridge. Photo: Why Edmonton

Find Out More:

A sample selection of Edmonton-based, Indigenous-led or Indigenous-focused organizations that celebrate and support the community.

Alberta Native Friendship Centres Association

Bent Arrow Traditional Healing Society

Racial segregation occurred throughout the 1920s in places like public pools, theatres, and restaurants in Edmonton, which restricted movement for racialized people.

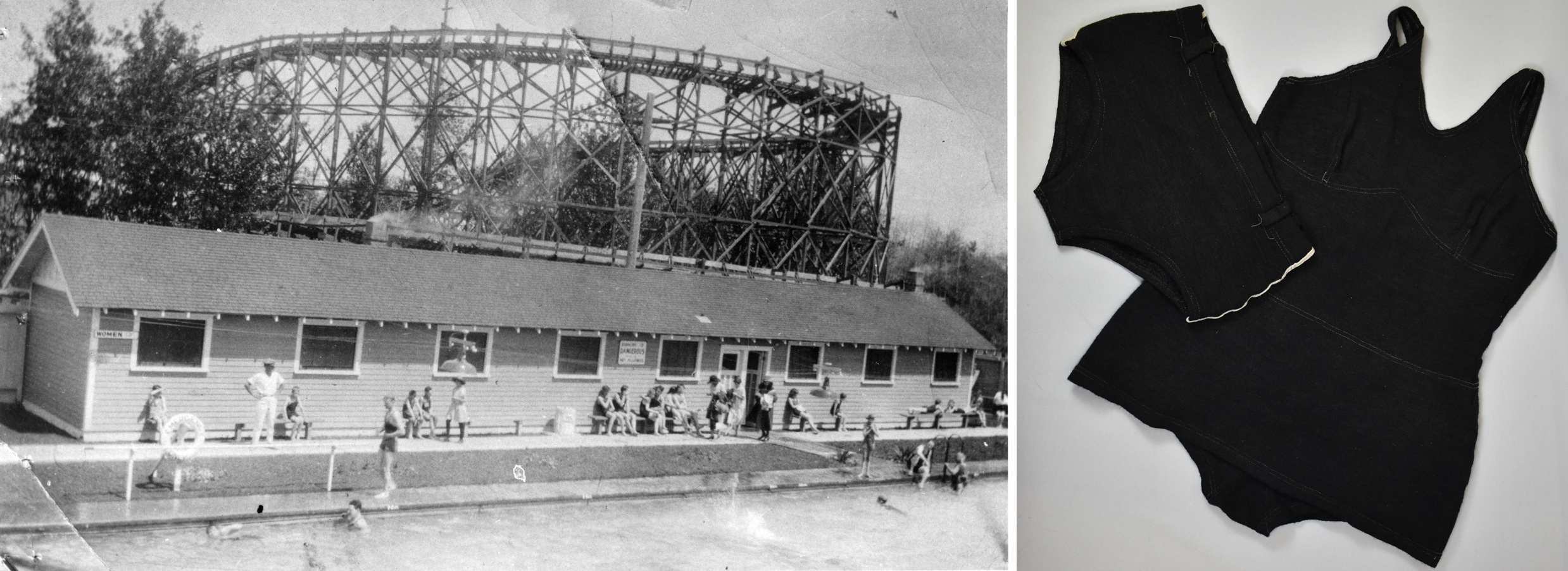

A public swimming pool was installed in Riverside Park in 1922, in the location where the Indigenous Art Park is now. It was surrounded by picnic areas, boardwalks, a band shell, and a fenced area with two moose. Another public swimming pool was located in Borden Park in 1924 alongside a roller coaster, a zoo, a carousel, and a tearoom.

Both of these so-called “public” swimming pools refused access to Black citizens in accordance with a city commissioner's order issued in 1923. Through the dedicated efforts of Black community organizations and individuals who openly challenged, formally appealed, and petitioned such policies and practices, the order was overturned in a council vote in July 1924.

“It was here in Edmonton that we were barred from the city pool at Borden Park. The old Pantages Theatre would only allow us to sit in the balcony.” - E.A. Cobbs, African-American immigrant. Goyette, Linda & Jakeway Roemmich, Carolina (2004). Edmonton in Our Own Words. University of Alberta Press, p. 274.

Original sign from the Pantages Theatre. It didn’t fit in one photo because the sign is nearly 7 meters long! [City of Edmonton Heritage Collection 1993-023-0001]

Find Out More:

CBC: A century ago, Black Edmontonians fought for the right to swim at public pools

CBC: Lulu Anderson: The history and present of Black civil rights movement in Alberta

Visit Lulu’s Lane south of Jasper Avenue and west of 103 Street.

The Canadian government introduced the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1923, the latest in a series of identification and exclusionary policies towards Chinese people going back to at least 1885. This racist legislation significantly restricted the movement of Chinese people into Canada by prohibiting Chinese immigration outright. It also restricted freedom of movement for Chinese people already in Canada, including those who were born in Canada, by explicitly stating on their government-issued Chinese Identification Certificate that, “This certificate does not establish legal status in Canada.”

Through the persistent efforts of Chinese communities, the Act was repealed in 1947. In 2023, one hundred years later, the 1923-1947 exclusion of Chinese immigrants was designated as a national historic event.

During the 1920s and the time of the Exclusion Act, one of the few opportunities for Chinese people in Canada was owning or working in laundries.

Ever-increasing mass mono-cropping to be competitive in the unstable markets of the 1920s made significant alterations to the land, resulting in a loss of biodiversity. More and more land continued to be cleared and cultivated for farming, including people going north of Edmonton where there was still homestead land available. The now surveyed landscape was transformed square by square from natural parkland, forests, and wetlands into farmland. During the 1920s, there was a marked increase in the pace of this change.

Clear-cutting trees and land-tilling practices in the 1920s contributed to drought and loss of topsoil in the 1930s. In response, the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration formed and planted over 2000 km of tree shelter belts in partnership with the existing Prairie Shelterbelt Program. This program did successfully reduce soil erosion and increase moisture retention on farm lands, and also introduced many non-native tree species. Over time, mono-cropping, invasive species and livestock grazing made natural blends of flora such as native grasslands increasingly rare, forever altering the movements of wildlife, seeds, and pollination.

Economic factors drove farmers to alter and use more land. However, it also pushed farmers to continually improve seed and stock quality. Alberta is known for growing some of the world’s highest-quality grains and raising high-quality beef.

The Alberta Pacific Grain Trophy for the annual competition at the Edmonton Exhibition for the best registered seed wheat grown in Alberta 1928 [City of Edmonton Heritage Collection 1985-000-4124].

Find Out More:

Shelterbelts and the History of Sustainable Agriculture on the Prairies

Cars became more common in Edmonton throughout the 1920s, which led to an expansion of roadways. Building new roads to expand development, trade, and recreation also resulted in a loss of harmonious relationships with the land.

At the beginning of the 1920s, there was no road from Edmonton to Jasper. The quality of existing roads was questionable with very few being paved. Most roads were gravel, and some were dirt which was only passable subject to weather conditions.

With the goal of easily moving further into nature, groups like the Edmonton Automotive Club promoted building a road between Edmonton and Jasper. Other groups wanted better roads too. The United Farmers of Alberta, who were elected to the Alberta Legislature in 1921, wanted better roads to improve the movement of produce and other goods.

The road from Edmonton to Jasper was completed in 1923, providing more access than the existing train and river systems could. The pursuit of experiencing nature and moving goods between Edmonton and the Rocky Mountains by automobile came with litter, exhaust, and vehicle-to-animal collisions. This resulted in negative environmental impacts and interruptions to wildlife habitat unlike what had been experienced before.

At the same time, being able to travel into nature and see the beauty of the mountain parks inspired many to protect the land and its wildlife. The era of conservation and

sustainability came to the forefront.

The large amount of land and airspace in which airports carry out their activities impacts the movement of nature within that environment, causing a loss of natural systems.

From runways and a hangar at Blatchford (City Centre Airport) in the 1920s to the extensive infrastructure of the international airport south of Edmonton in later years, the number of acres of land required is large.

Activities include vehicle and aircraft movement and emissions, elimination and control of all flora for paved runways, high levels of noise and vibrations, frequent movement of high-density petroleum products, frequent import of foreign products which brings the risk of invasive species, and the presence of bright and flashing lights (started with torches to light runways in the early 1920s). All such activities impact the natural systems related to animal and bird movements, the ability of plant species to thrive, and water drainage.

In recent decades, many environmental and regenerative movements have responded to the climate crisis. There are lots of actions that people can take to help make a positive difference to the health of the planet and all of its inhabitants.

Find Out More:

Neighbouring For Climate is a City of Edmonton program to bring neighbours together to take action on climate change and make progress locally.

Ărramăt is a University of Alberta project of Indigenous organizations, governments, university researchers and other resource people working together on research and action in support of the health and well-being of the environment and people.

Conclusion

The 1920s saw significant growth in modes of transportation resulting in increased freedom of movement, but only for some and with costs.

One hundred years later years later in the 2020s people are moving even faster and more frequently than ever before. Equity of movement within society is improving, but still has a long way to go. The earth’s biodiversity and natural systems continue to pay the price, but there is also hope through growing climate justice movements and regenerative thinking that seek to re-establish good relationships of people with the land. These may become the most important movements in the next 100 years.